By Cheryl Cranick, Honors Program

In September, Robert Holster ’68 witnessed the culmination of his generosity: the first Holster Scholar presentations. His $1 million gift, given jointly by his wife Carlotta ’68, funds the Holster Scholar First Year Project, sponsoring Honors student research. But it has a unique qualification: the grants are given to first years.

Holster felt giving back was an “obligation,” crediting UConn Honors as “fundamental to getting me off to a good start,” he said. He was a member of the inaugural Honors class in 1964.

The seven 2011 Holster Scholars were selected through a competitive application process. They committed to an introductory research course, self-designed summer research projects, scholarly deliverables, and presentations. Their guide through the process was Dr. Jill Deans, Director of the Office of National Scholarships. Each student also worked with an individual advisor. The students were responsible for the research, but their mentors “taught them what it means to be a scholar,” said Deans.

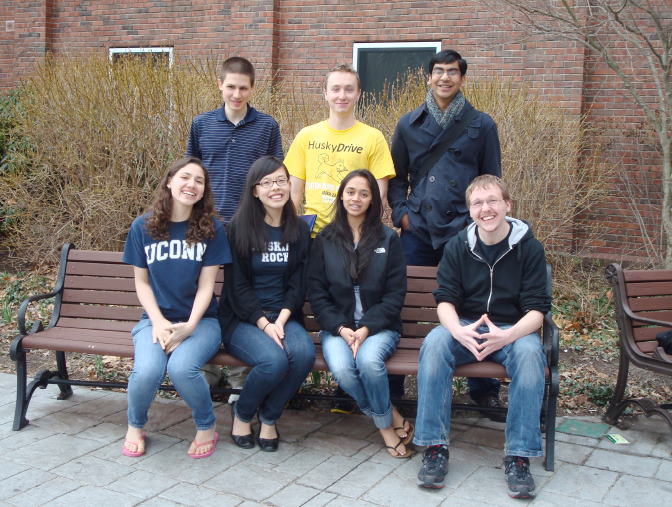

(left) Nikhil Shah ’14, Ye Sun ’14, Robert Byron Bunda ’14, Robert Holster ’68, Rebecca D’Angelo ’14, David Schwegman ’13, Kousanee Chheda ’14, and John Giardina ’14For some of the students, this was the first time they had done research. Others had varying levels of experience, but had never taken the lead on a project. The topics, like the interests of Honors students, were diverse.

In his Holster application, David Schwegman ’13 (history) recalled his first year of high school when he met a genocide refugee from the Balkans. As a Holster Scholar, Schwegman explored another conflict, the 1972 Burundi genocide in Africa. “The Holster grant gives you the freedom [to follow your research],” he said. Schwegman tracked the social, economic, and political motivations for the deaths and said the conflict is one history has mostly forgotten.

Rebecca D’Angelo ’14 (anthropology) investigated a whaling vessel anomaly through 20th century archives. She wondered why schooners were used to travel from New London, Conn., to Desolation Island, off the coast of Antarctica. Her answer was elephant seals—animals that lived alongside whales, yet also left the sea, moved slowly on shore, and yielded higher-quality oil. To reach them, crews needed smaller ships. D’Angelo concluded that sealing became a “land-based adaptation” of Connecticut’s whaling industry.

John Giardina ’14 (economics; molecular and cell biology) wondered how diet affects heart health and the long-term costs of coronary heart disease. Using recent national health survey results, he calculated risk based on original and manipulated diet factors. He found only minor differences, but called for future long-term study of the diet variable, including its relation to gender. Giardina hypothesized that the increased risk for men may result from dietary preferences, claiming women eat healthier on average.

Ye Sun ’14 (biological science) was inspired to study science beyond the lab. She applied epidemiology—the mapping of health patterns—to PCB (polychlorinated biphenyls) exposure and its link to breast cancer. Her meta-analysis of existing studies showed weak correlation, though she also noted her scientific limitations: date, duration, and depth of exposure were unknown. She suggested further investigation, but expressed her excitement toward the subject as she looks ahead to her medical career.

Robert Byron Bunda ’14 (management) knew he wouldn’t take a business class until his junior year. But that didn’t stop him from developing a plan for a student-to-student personal training business at UConn. He just had to figure out the process from nothing. He read business resources, interviewed professionals, and devised a market research survey. He eventually learned to think like an entrepreneur and ask every question that might affect his bottom line.

Kousanee Chheda ’14 (molecular and cell biology) researched the effects of hyperbaric oxygen therapy on gene expression, which could benefit surgery procedures and disease treatment. She exposed mice to varying levels of oxygen and examined their tissue. A limitation of her study is the human body itself, citing genes may react differently and alter the effectiveness of the therapy. But the project taught her the demands of conducting an experiment, not just applying the science.

“[Earth is] called the blue marble because there’s so much water there,” said Nikhil Shah ’14 (environmental engineering), yet so many people do not have clean water. In Africa, 32 percent of the population is without improved water sources; that number is 62 percent in Ethiopia, he said. Shah developed an osmosis experiment to filter water through iron. But clogging increased the need for more iron, making the process too costly for local needs. Shah plans to explore other variations: “I need to question my assumptions.” His trip to Ethiopia this winter should serve as motivation.

By the end of the summer, the students had accomplished the goals of the scholarship. They advanced their knowledge and inched closer to becoming experts. They developed skills in critical thinking, communication, and leadership. But another lesson was mentioned repeatedly: “You need to be flexible because things will go wrong,” said Schwegman, who was not the only one to make project modifications. Chheda mirrored the sentiment: “Don’t be discouraged by it,” she said.

Dr. Lynne Goodstein, Director of the Honors Program, acknowledged the success of the first cohort. “I am grateful to you for taking this so seriously,” she said. “You set the bar high.” She also reiterated the tremendous generosity of the Holsters. “This gift is a permanent part of what we do. As long as there’s an Honors Program, we will have a Holster Program,” said Goodstein. “That’s a legacy.”

Deans is already recruiting for the new cohort of Holster Scholars. “It was created just for you,” she said to the first-year students who attended the presentations. Chheda further emphasized the accessibility of the grant, noting previous research experience is not a prerequisite.

Taking the stage at the end of the event, Deans made expressions of thanks to all who participated. Then she read a passage sent to her that day by a colleague, quoting National Public Radio host Ira Glass: “Nobody tells this to people who are beginners. … All of us who do creative work, we get into it because we have good taste. … For the first couple years you make stuff, it’s just not that good. … And your taste is why your work disappoints you. A lot of people never get past this phase, they quit. … It is only by going through a volume of work that you will close that gap, and your work will be as good as your ambitions. … You’ve just gotta fight your way through.”

“They all fought through it,” Deans said of the young scholars, “and I cannot wait to see the whole volume down the road.”

Return to the Fall 2011 issue of the Honors Alumni eNewsletter